DDW explores ‘Elvis’ Baz Luhrmann’s impossible film and how a message of madness and lost love took centre stage over the key figures in Presley’s later life.

“Elvis did not curl into a fetal position and give up on life in 1973,” wrote Linda Thompson – the Grammy-Award-winning songwriter and once live-in girlfriend of the King of Rock and Roll. “He had more years of happiness”.

The testimony, reported on by the Express, seemed to appear then disappear in the blink of an eye. It served as the caption in a now-deleted Instagram post depicting an uncharacteristically healthy-looking Presley in Hawaii with Thompson – not Priscilla – by his side.

Whether on social media or through her own book A Little Thing Called Life, Thompson’s words are all that she has left when it comes to her story with Elvis. The King isn’t alive to set the record straight and according to the multi-million dollar Baz Luhrmann film, Linda Thompson never existed. “I wouldn’t call it a biopic,” Thompson told an interviewer in the days following the film’s release citing the people who weren’t included that were exceptionally important and instrumental in Elvis’ life.

Thompson, as well as Presley’s final partner Ginger Alden, and his close confidant and cousin Billy Smith, were neither consulted in the making of the film nor invited to screenings or the well-publicised premiere. While Smith at least appears in the film – albeit for a “blink and you’ll miss it” moment, Thompson and Alden are replaced by nameless placeholder brunettes and caramel blondes.

It was Thompson that was with Elvis as he shot up the television set. In Elvis, the moment serves as an example of Presley’s developing paranoia, but for Thompson, it was simply a case of impestuous megalomania. He didn’t like the way Robert Goulet was singing “If Ever I Would Leave You”.

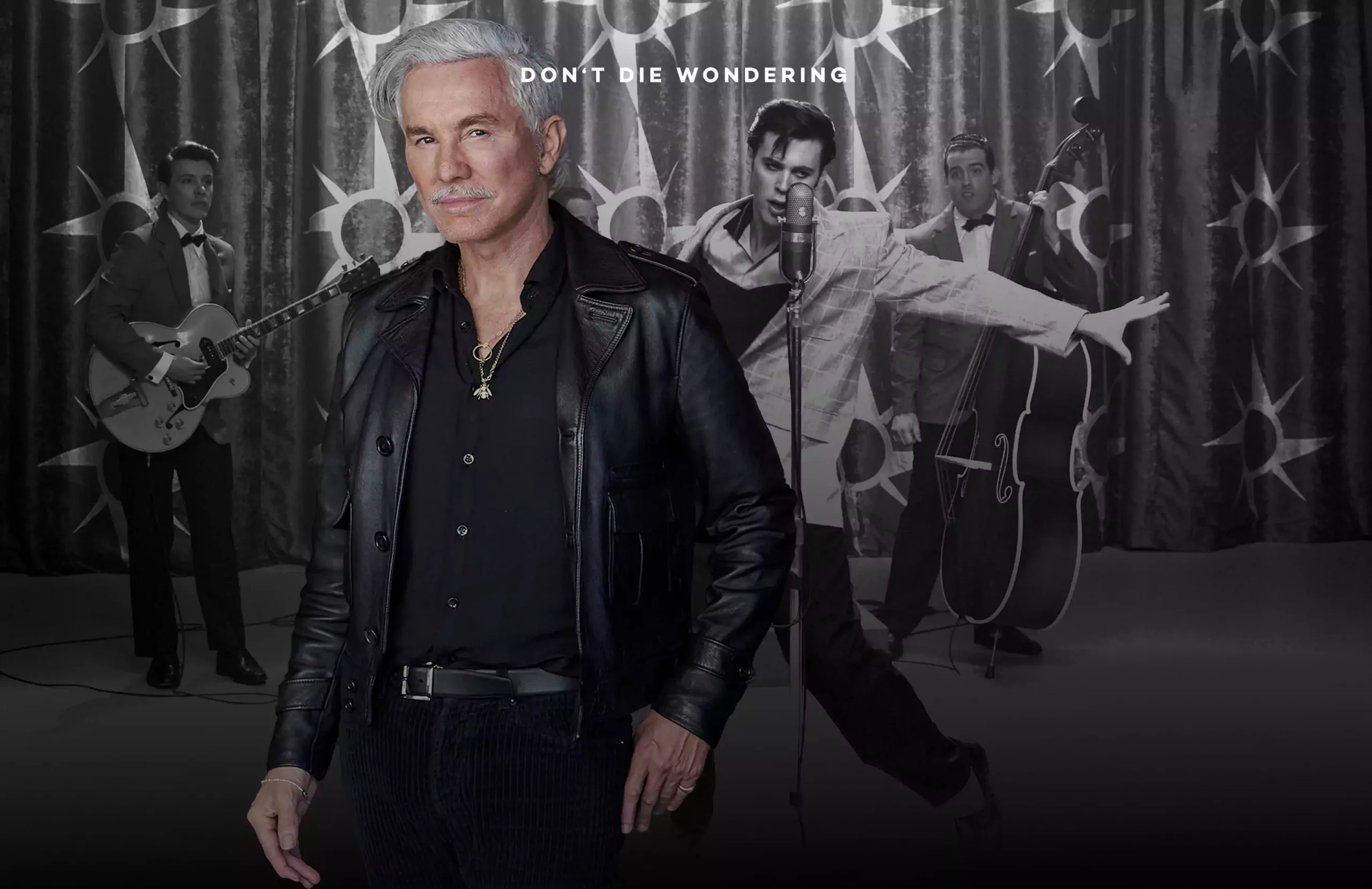

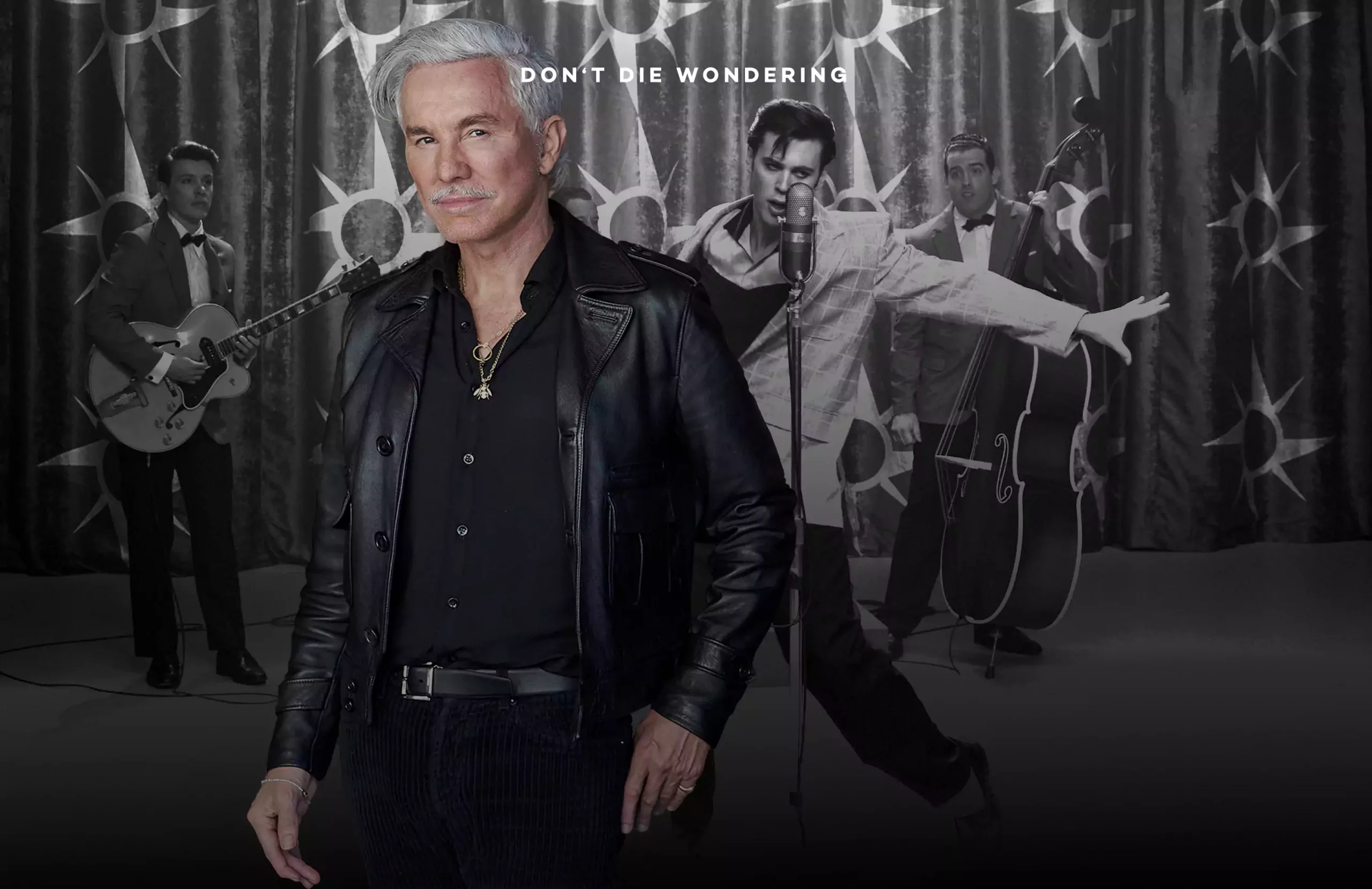

It was showing on the TV. He politely asked Thompson to leave, and when she did he shot three times. It was Thompson that had to make the call to get him a new TV. For Luhrmann, this level of biographical detail feels impossible given the art form. “I mean you’re telling a 42-year-long life in two-and-a-half hours”, the director tells IndieWire’s Anne Thompson while addressing his unconventional approach to the biopic form. “There’s dramatic license and there’s compressions because you’ve got to compress times”.

Yet with a four-hour long directors cut in existence that explores Elvis’ first relationship with Dixie and his later visits with Nixon, the exclusion of Presley’s two successive life partners after Priscilla is wounding to the women who stood by him. Alden and Thompson were not listed in scripts and were never mentioned in casting press discussions, despite Alden being the one who found Elvis’ body and Thompson being one of the first people Lisa Marie called with the news.

As the denouement of the film whizzes past us, Elvis crumbles and dies after the dissolution of his marriage – spiralling with addiction, betrayal and lost love. The tragedy, according to Luhrmann, was a man with a hole in his heart “constantly looking and searching for love and finding it on stage but nowhere else.”

It proved improbable for Luhrmann’s broken divorced Elvis to move on to a five-year relationship with Thompson and an engagement with Alden, yet that’s exactly what the King of Rock and Roll did. For Alden in particular, the representation of Elvis as a depressed, run-down man was torturous. “Some people dared to dismiss the last year of Elvis’s life as a runaway train toward suicide,” wrote Ginger Alden of the myths associated with Elvis’ final chapter.

In the nine months Alden spent with Presley before his death, Elvis proved to be full of life and all it’s possibilities. He practiced karate and spent days upon end with Alden reading books of Eastern philosophy and religion. His favourite at the time was Autobiography of a Yogi by Paramahansa Yogananda and Presley took special care to explain his understanding of chakra and kundalini to the Tenessee native twenty years his junior. Elvis was “enthusiastically making plans for the future as he endeavoured to transform his dreams into a reality”, remembers Alden, “a reality that included marrying me.”

Baz Luhrmann seemed like a natural choice to broach the impenetrable cultural icon of Elvis Presley. Elvis offered a movement away from the Shakespearean grandeur of Romeo + Juliet and the hyperbolic tragedy of Moulin Rouge. For an auteur like Luhrmann, Presley presented an unbelievably true story of a young boy born in Tupelo, Mississippi that rose to previously unimaginable fame. The biographical element invited Luhrmann to explore a markedly softer, more human, and intimate approach, while Presley’s prolific musicianship still provided a bombastic musical catalogue and the scope for a truly monumental soundtrack.

Despite doubts and numerous catastrophic hurdles (remember when Tom Hanks got Covid?), Elvis persevered and premiered in Cannes on the 25th May 2022 to a 12-minute standing ovation. Warner Bros’ huge financial gamble seemed to pay off, as fifteen years of work was realised with Priscilla and Lisa Marie Presley’s enthusiastic approval.

Critical acclaim was expected, particularly with such a well-studied performance from newcomer Austin Butler as the King, a dramatic challenge only previously accepted by the likes of Jack White and Jonathan Rhys Meyers. Yet the reviews rolled in for Luhrmann and proved as divisive as ever. ‘“Elvis”, wrote Richard Brody in the New Yorker, “is a Wikipedia Entry Directed by Baz Luhrmann”. Peter Bradshaw concluded similarly.

“It was not a movie so much as a 159-minute trailer for a film called Elvis,” he said echoing an earlier Guardian criticism of Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby that focused on the unexplored titular subject of the film. The same issues that have followed Baz Lurhman since his sophomore outing of Romeo + Juliet arose once again. Issues of accuracy were raised, alongside misrepresentation of the source material.

Luhrmann’s sense of style and beauty was viewed to have superseded basic ideals of narrative and sense. Critics felt distanced from Elvis’ titular subject while facts and characters were omitted to tell an auteur’s vision of the story. Even if Baz Luhrmann was exploring a new approach to the biographical genre, his process proved increasingly hard to justify when Elvis was being marketed as a form of nonfiction.

Toward the very end of the film, Presley’s death is announced by newspaper headlines visibly puncturing the screen around Butler’s Elvis-chapped face. He had just discussed rehab with Priscilla and told her that he will always love her. The scene as presented is never documented to have happened, although the sentiment of “get help” and “I love you” was shared between Elvis’ numerous friends and partners.

Then in a moment designed to evoke an emotional response, Butler appears in prosthetics and padding to recreate footage of the final television special Elvis in Concert. Butler’s struggling Presley begins singing valiantly through ‘Unchained Melody’ as the film dissolves into reality. The archival footage plays and as the music swells, there is a montage of the real Elvis through the years set to his acceptance speech for the 1970’s Ten Outstanding Young Men of the Nation Award.

“When I was a child, ladies and gentlemen, I was a dreamer,” the real Elvis can be heard saying. “I read comic books and I was the hero of the comic book, I saw movies and I was the hero in the movie.” Parker is seen taking his last breath, sublimely pictured in a hyper-isolation as the screen fades to black and the intertitles explain the fallout of Parker’s actions and Elvis’ life.

There is a realisation that the most traumatic scene of Elvis’ life – his final moments and his final breath – will be left offscreen. The raw yet unsavoury image of Elvis suffering a heart attack is bypassed alongside his final moments playing Raquetball with his cousin Billy before reading beside a sleeping Ginger.

Elvis’ final setting is sanitised and the glitzless latrine-based reality of dying from a heart attack isn’t alluded to or even mentioned. “Elvis is dead” is a much neater headline for a story that refuses to challenge the complex nature of its subject. Presley’s final day was one of perfect normalcy, a rightful end for a man who had been deified, vilified and depersonalised for his whole career.

The story of Elvis deserves care. It deserves to be stripped at times from Luhrmann’s Liberace-Esque dazzle. Behind the quiffs, the “uh-huh”s, and the white jumpsuits of the Vegas Wedding Chapel is a man that deserves to be as realistically depicted as the gaudy bling of his art.

There must be a firm recognition that Elvis – although immensely talented – was a physically and emotionally flawed individual capable of shooting at will, eating to excess and practicing karate at the same hour. Despite Luhrmann’s aestheticism, Elvis Presley was not always beautiful – but his complex and exuberant life continued in technicolour for the years after Aloha from Hawaii, right until the moment of his death.